There isn’t a more confounding photographic printing method under the sun than the gum bichromate process: indeterminate results, constantly changing strategies, materials that vary from one batch to the next, atmospheric changes from day to day and season to season…Don’t get me started on making negatives. And then there’s the time it takes to finish one.

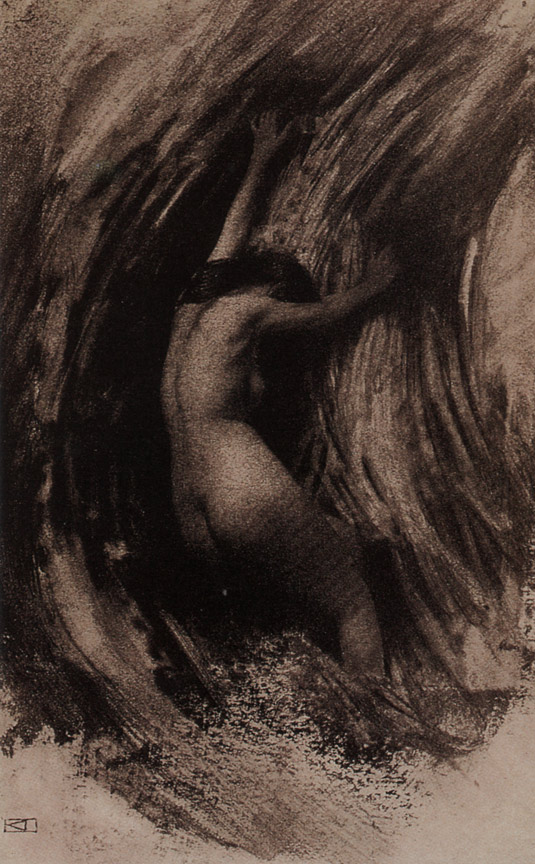

Where photography excels at capturing moments, a gum print of that photograph can take weeks to complete. But for all that, gum printing offers a highly expressive, personal medium for reproducing photographic moments into one-of-a-kind works of art. Gum renders photographs a haunting beauty as well as depth of surface character that is uncommon in the world of photography.

The Pictorialist Movement

The process came of age in the 1880s, a photographic response to the Arts and Crafts Movement that had been preaching the value of hand-crafted vs. mass-produced items for a couple of decades. Post-Impressionism and the Symbolists were having their day in the world of art as well. Those influences are more than evident in early gum history.

The Pictorialist Period in photography’s history (1886-1920) featured many different printing processes other than the silver gelatin print that we think of as black and white photography. Alternative processes like gum, platinum, photogravure, and cyanotype offered an opportunity to extend the photographic moment beyond a faithful rendering taken in the camera to a uniquely layered hand-made print.

Pushing Boundaries

Those alternative processes were among the first to break the glass ceiling that had hung over photography since its birth – admittance and acceptance within the world of art. Photography has claimed its place there ever since. But the inherent flexibility of the gum process and liberation from predefined outcomes allowed gummists to veer farthest from the acceptable canon of the time. Gum prints made their world debut at the Première Exposition d’Art Photographique (First Exhibition of Pictorial Photography). They created a storm of criticism. Some wondered if gum prints could even be considered photography. They charged that gum printing more resembled drawing or painting than photography. Critics said that there was too much of the artist’s hand.

For me that’s one of the features of gum printing. Gum prints are not photographs made at the push of a button. There’s more than enough of those in the world for my taste. I like the flexible outcomes it allows. The freedom from pre-determined looks. The ability to transform a photograph into something unique. I’m enchanted by the alchemist’s dream of turning lead into gold. The transformation of one thing into another thing. Making gum prints offers me a place in that dream.